After extended use, Windows 10 or 11 systems often accumulate excess, outdated device drivers. Discover how to declutter your Windows driver store by employing Driver Store Explorer and straightforward methods to eliminate old or unneeded components.

As Windows machines age, older device drivers are invariably replaced by newer versions. Even without diligent maintenance, Windows Update usually installs new drivers for at least a dozen devices each year.

Users who prioritize having the latest drivers might also utilize utilities like the Intel Driver & Support Assistant (DSA), the NVIDIA App (for graphics, audio, and 3D drivers), or comprehensive driver management solutions such as ioBit’s Driver Booster or the Snappy Driver Installer project from SourceForge to verify and update drivers on Windows 10 or 11 systems. While Intel and Nvidia tools focus on their proprietary hardware, universal driver update tools scan all components and suggest newer versions, offering different levels of assistance for installation.

Crucially, neither specialized nor general driver update utilities eliminate old drivers when installing new ones. Consequently, while these tools are effective at updating drivers, they fail to mitigate driver bloat. The Intel DSA, in particular, is noted for significantly contributing to this issue, as will be demonstrated further in this article.

Redundant device drivers occupy valuable storage and can potentially degrade system performance. Therefore, routinely purging obsolete files is an essential PC maintenance task.

Prior to detailing the removal process, let’s examine the steps involved in a Windows driver installation.

How does a Windows driver installation work?

The installation process is surprisingly intricate, involving numerous hidden operations within Windows. For our purposes, we’ll focus on Plug and Play (PnP) devices, which are designed to self-identify to Windows, enabling the OS to help locate a suitable, though not necessarily the newest, driver. This information is drawn from the excellent Microsoft Press publication, Windows Internals (currently in its 7th edition across two volumes).

Here’s the process:

- During enumeration, a bus driver notifies the PnP manager of a discovered device, providing its device instance identifier (DIID).

- The PnP manager then searches the registry for a matching function driver. If none is found, it relays information about the device, including its DIID, to the user-mode PnP manager.

- The user-mode PnP manager attempts an automatic installation without requiring user interaction. If the installation process necessitates dialog boxes for user input, the PnP manager will launch a Hardware Installation Wizard to manage these tasks, provided the logged-in user has administrative rights. (Otherwise, this action will be postponed until an administrator logs in.)

- The Hardware Installation Wizard employs Setup and CfgMgr (Configuration Manager) API functions to pinpoint INF files compatible with the detected device. Typically, this involves retrieving these files from the local file system (or from media such as a CD or DVD) as directed by the user.

- The installation unfolds in two phases: (a) A third-party driver installer adds a driver package to the driver store, and (b) the operating system executes the actual driver installation via the Drvinst.exe process (located in %SystemRoot%System32). During this, .inf and .cat files are placed in the driver store, linked to a DIID structured as oemnnn.inf, where nnn is a one- to three-digit decimal index. (To ascertain this nnn index for any driver in the store, you’ll need NirSoft’s superior DriverView utility, as the tool discussed later in this article does not provide it.)

As documented, this driver management sequence makes no mention of clearing out older drivers from the Windows driver store (found at %SystemRoot%System32DriverStoreFileRepository). Consequently, this guide will concentrate on examining the driver store’s contents and deleting aged or redundant files to minimize its storage usage.

Important Caution! A significant drawback to consider when deleting items from the driver store is that if you keep only the most current driver(s), the ‘Roll Back Driver’ feature in Device Manager’s Properties window for that device will become unavailable. This function is typically provided to allow users to revert to a previous, stable driver version if the current one causes issues.

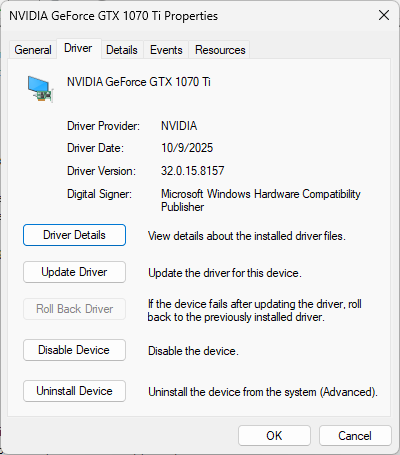

In fact, if only a single driver version exists for a Windows device, the Roll Back Driver button will appear grayed out and inactive (refer to Figure 1) within its properties.

Figure 1: With only one driver version in the Windows Store, the rollback option is disabled.

Ed Tittel / Foundry

A safer strategy for tidying your driver store could involve retaining the two most recent drivers for any particular device, instead of just the latest one. Personally, I only adopt this for frequently updated or beta drivers. However, for those managing deployment images, this recommendation is crucial when testing drivers (and potential deployment images). Nonetheless, all superfluous files, including redundant or outdated drivers, must be removed from images before deployment.

Understanding Device Drivers in Windows 10 and 11

For contemporary Windows operating systems (10 and 11), a highly effective utility exists for direct observation and management of the Windows driver store. This tool, originating from GitHub, is known as Driver Store Explorer (or RAPR.exe). Version 0.12.135, which is the latest iteration at the time of this publication, performs admirably on both Windows 10 and 11.

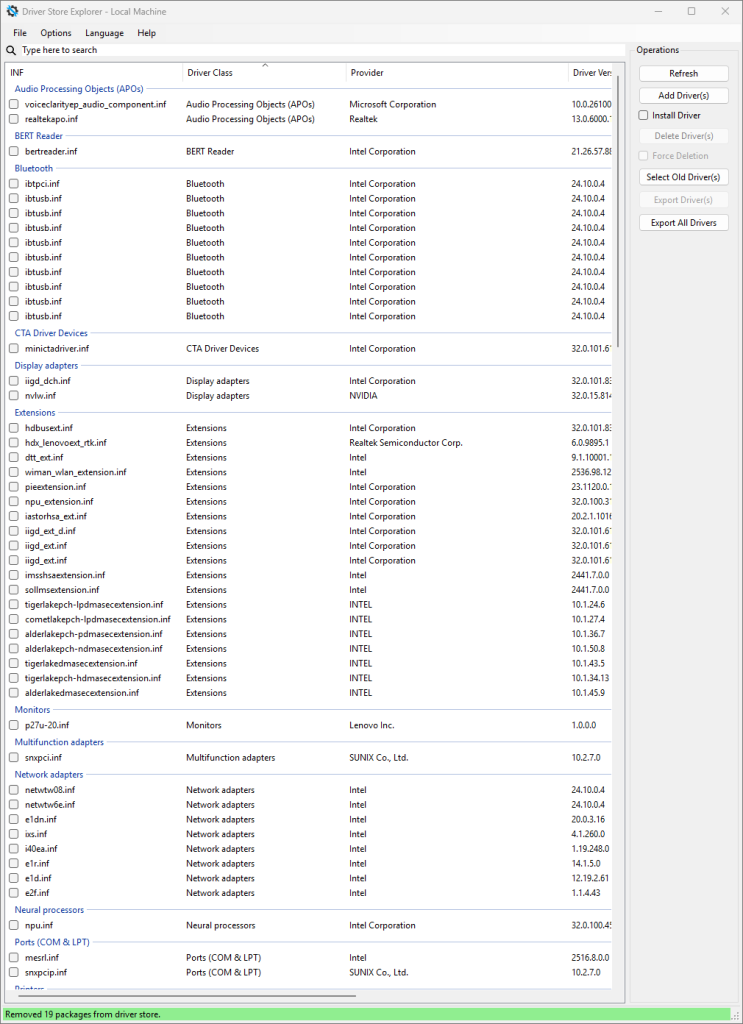

To interact with the driver store, you need to launch RAPR.exe with administrative rights (by right-clicking the executable and choosing “Run as administrator” from the contextual menu). Following this, you must list the contents of the driver store, which will generate a view similar to Figure 2.

Figure 2 illustrates the driver store of my Lenovo ThinkStation P3 Ultra 2 following a cleanup using RAPR. Initially, it contained 925 drivers; after the cleanup, 906 remained, indicating 19 removals. This action decreased the Driver Store’s size from 6.44GB to 5.91GB, freeing up 0.53GB of disk space, as reported by the properties of the FileRepository folder. Further manual deletion of duplicate entries reduced the count to 897, and the size to 5.87GB (an extra 0.04GB saved, for a grand total of 0.57GB).

Figure 2: Post-cleanup, the P3 Ultra shed 19 drivers; an additional 9 were removed by deleting duplicates.

Ed Tittel / Foundry

To offer perspective on how this driver file repository can grow, I’ve observed the total item count on this very machine reach 1200, with over 150 of those being redundant Intel drivers, primarily for Bluetooth or Wi-Fi. Clicking any column header in this view will reorder the list according to the values in that specific column.

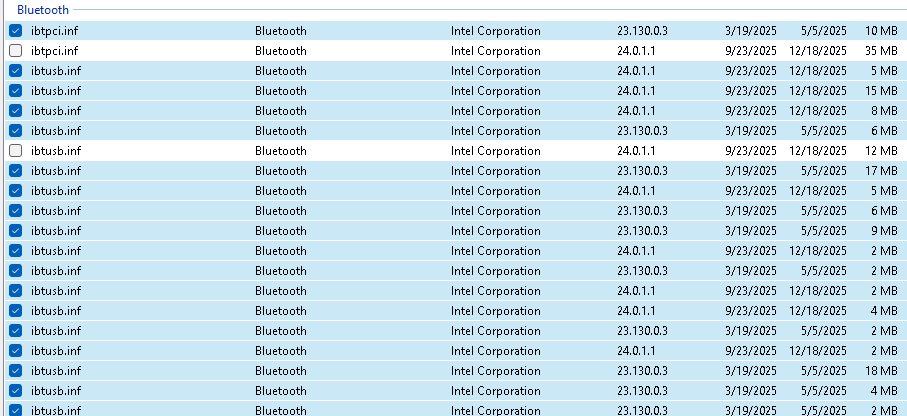

As noted previously, the Intel DSA and Nvidia applications are major contributors to driver bloat. Intel’s tool, in particular, frequently installs numerous copies of identical drivers into the driver store. For instance, my cleanup example in Figure 3 illustrates seven instances for each of two Bluetooth USB devices. All are labeled “ibtusb.inf” because the system in question features two distinct sets of USB ports, each requiring its own driver instance.

Important: For reasons unknown, if your PC contains multiple instances of a device, you truly need a distinct copy of its driver package (oemnnn.inf) for each. This is why you shouldn’t automatically delete what appears to be redundant copies of the same driver. However, an excessive number of identical drivers — or even more problematic, multiple versions of drivers for the same device — typically signals a need for cleanup. Luckily, RAPR can automate this process for you.

Removing Unnecessary Drivers with RAPR

To remove outdated drivers, simply click the Select Old Driver(s) button located in the top right corner, and then proceed to click Delete Driver(s). RAPR will manage the remainder of the task automatically.

Rest assured, RAPR will not remove any drivers that are actively in use. The “Force Deletion” option exists for such scenarios, but it’s rarely necessary. My personal use of RAPR’s force delete function has been limited to instances where widely accepted advice recommended removing a problematic or suspicious driver to substitute it with an alternative, functional, older version. This situation tends to occur more frequently with printer drivers, for unknown reasons.

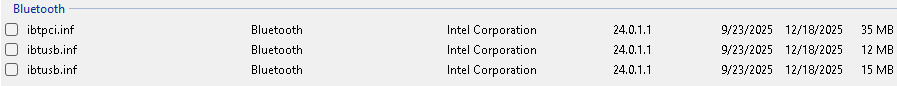

Figures 3 and 4 present a before-and-after comparison, demonstrating the typical outcomes of these cleanup procedures.

Figure 3: On the P3 Ultra, 18 instances of ibtusb.inf and two of ibtpci.inf are visible.

Ed Tittel / Foundry

Figure 4: Following cleanup, only two copies of itbusb.inf and one of ibtpci.inf remain.

Ed Tittel / Foundry

Each distinct device necessitates its own driver instance. In the case of the P3 Ultra, it features two sets of Bluetooth USB devices, meaning two drivers persist even after attempts to remove one. Given that common graphics adapters can be over 1GB in size, and standard device drivers typically range from 2MB to 35MB, it becomes clear how eliminating superfluous entries can significantly reclaim disk space.

An important detail regarding RAPR is that if a system contains multiple copies of the identical, current driver, the Select (Old Drivers) option will not automatically remove them. In these situations, manual deletion is required. My practice is to address these section by section, retaining the most recent instance of the driver. This method has proven quite effective.

A Special Note on Windows Printer Drivers: Past and Present

In March 2021, Microsoft rolled out its Universal Print architecture. Consequently, the majority of printers now function with a standardized, straightforward set of print drivers. These drivers are readily acquired and kept current via Windows Update, providing consistent and effective performance. However, for systems or networks utilizing legacy printers, it remains necessary to visit the manufacturer’s website to download drivers specifically designed for those particular printers (and sometimes their unique configurations).

Legacy printer drivers can be particularly persistent, resisting removal even with RAPR’s force deletion option. The key is to disconnect or make the printer invisible to the PC before attempting driver modifications. This makes the removal of old drivers significantly easier. Moreover, new drivers will almost certainly install automatically once you reconnect to or establish a link with the printers you intend to update. Take this as a helpful tip.

When to Perform Driver Store Cleanup

An age-old internet adage, ‘YMMV’ (Your Mileage May Vary), is equally pertinent to optimizing and cleaning Windows systems. It signifies that diverse systems or deployment images will demonstrate varied characteristics, performance metrics, and so on.

Bearing this in mind, check the properties of your driver store directory: if it surpasses 5GB on Windows 10 or 10GB on Windows 11, I recommend running RAPR to scan for unnecessary files. If it exceeds 8GB on Win10 or 15GB on Win11, it’s absolutely crucial to investigate its contents and remove any unwanted or redundant items. I’ve encountered cases where this folder swelled beyond 20GB – believe me, you want to prevent it from reaching such extremes.

Admins, take note: When refreshing a deployment image for distribution, you’ll frequently update components within the driver store. Since this process doesn’t inherently purge older entries as new ones are added, you must utilize RAPR (or comparable command-line utilities) to eliminate redundant and outdated items. The only situation more detrimental than a single PC having superfluous, unneeded drivers is having those same unnecessary copies multiplied across every image deployed within your organization!

Given that Nvidia display drivers often take up 2 to 2.5GB per version, retaining outdated drivers is a significant waste of storage. For added security, you could choose to keep two versions (by simply deselecting the second-most-recent version after using RAPR’s Select Old Driver(s) feature), but there’s no logical need for more than two in the driver store. An optimized and verified deployment image should only contain the necessary number of driver copies. (Prior to adopting routine cleanups, I would often discover a dozen or more Nvidia display drivers on a PC running an OS image that was one to two years old.)

As a rule, I schedule quarterly driver cleanups via calendar reminders. However, in practice, I often review them more frequently. It’s common for me to run RAPR after each Patch Tuesday to monitor any changes on my systems. Naturally, you’re free to establish your own routine – but aim to perform this task at least once or twice annually.

It takes considerable effort to cause harm using RAPR, so you shouldn’t feel obligated to create an image backup prior to cleaning your driver store. Nevertheless, being a ‘belt-and-suspenders’ individual, I’ve adopted this habit as a precaution, in case I inadvertently delete something essential. Should an overly zealous cleanup leave you with a malfunctioning or unbootable machine, you can always restore that backup from your PC’s repair/recovery media. (Alternatively, many backup solutions, like Macrium Reflect Free, allow you to mount the old image as a VM and extract the necessary drivers from its driver store using RAPR’s export and installation functions.)

Who knows? Either approach might prove useful. With a backup in place, you can confidently perform any cleanup tasks, anytime, without apprehension.

This piece was initially released in November 2015 and saw its latest revision in January 2026.