When millions click simultaneously, auto-scaling alone won’t suffice — robust systems thrive through strategic load shedding, isolation, and rigorous real-world drills.

In the realm of streaming, major events like the “Super Bowl” transcend a mere game. They represent a real-time, high-stakes distributed systems stress test observed by tens of millions globally.

When I oversee infrastructure for significant occasions—be it the Olympics, a Premier League fixture, or a season finale—I confront a “thundering herd” scenario that few systems ever encounter. Millions of users log in, browse, and initiate playback within the same tight, three-minute window.

Yet, this immense challenge isn’t exclusive to media. It mirrors the digital nightmare that preoccupies e-commerce CTOs before Black Friday or financial systems architects during a market collapse. The core issue remains constant: How does a system endure when demand surpasses its capacity by orders of magnitude?

Most engineering teams instinctively lean on auto-scaling as their salvation. However, at the “Super Bowl standard” of scale, auto-scaling proves insufficient. It’s inherently too reactive. By the time your cloud provider provisions new instances, system latency has already soared, your database connection pool is depleted, and users are greeted by a dreaded 500 error.

Presented here are four essential architectural patterns we employ to manage extreme concurrency effectively. These strategies are applicable whether you’re streaming crucial sports moments or handling checkout surges for exclusive product releases.

1. Strategic Load Shedding

The most significant error engineers make is attempting to process every single request received by the load balancer. During a high-concurrency event, this approach is self-destructive. If your system’s peak capacity is 100,000 requests per second (RPS) and it’s suddenly hit with 120,000 RPS, striving to serve everyone typically leads to the database freezing and ultimately, zero users being served successfully.

We implement load shedding decisions based on business criticality. It is far more effective to perfectly serve 100,000 users while temporarily asking 20,000 others to “please wait” than to witness the entire site collapse for all 120,000.

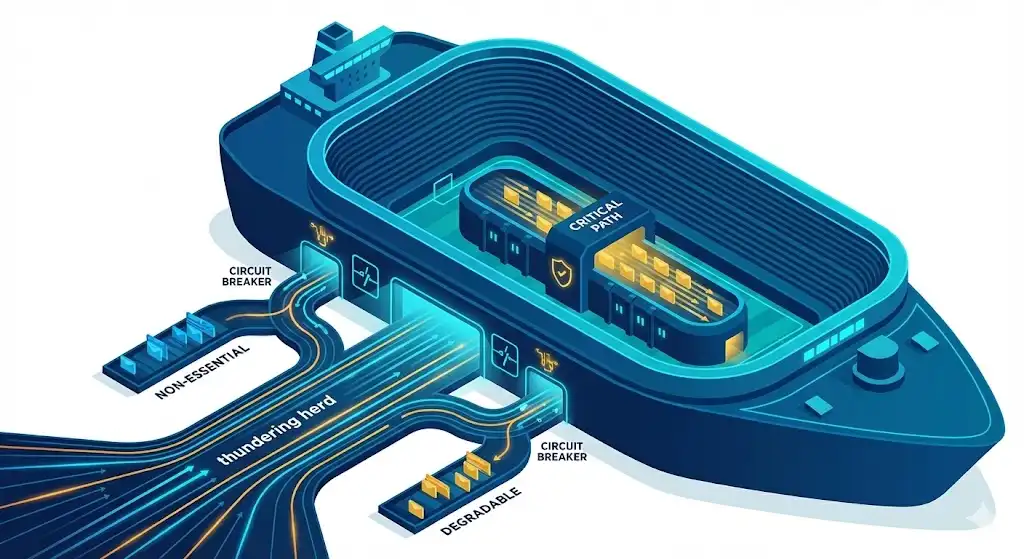

This methodology requires categorizing traffic at the gateway layer into distinct priority tiers:

- Tier 1 (Critical): Functions like Login, Video Playback (or for e-commerce: Checkout, Inventory Lock). These requests are absolutely indispensable and must succeed.

- Tier 2 (Degradable): Services such as Search, Content Discovery, and User Profile edits. These can tolerate being served from slightly outdated cached data.

- Tier 3 (Non-Essential): Features like Recommendations, “People also bought” suggestions, and Social feeds. These can gracefully fail or be omitted without significant impact on core functionality.

We utilize adaptive concurrency limits to detect increases in downstream latency. As soon as a database response time surpasses a predefined threshold (e.g., 50ms), the system automatically ceases calls to Tier 3 services. The user might encounter a more simplified homepage, but essential actions like video playback or purchase completion proceed uninterrupted.

For any high-traffic system, it is crucial to explicitly define your “degraded mode.” If you fail to decide what functionalities to disable during a traffic surge, the system will invariably make that decision for you, often by shutting down everything.

2. Bulkheads and Blast Radius Isolation

Manoj Yerrasani

Similar to a cruise ship’s hull, which is divided into watertight bulkheads to contain flooding in one section and keep the vessel afloat, distributed systems often, by oversight, resemble ships constructed without such internal divisions.

I’ve witnessed catastrophic outages triggered by seemingly minor features. For instance, if a third-party API providing “user avatars” becomes unavailable, and the “Login” service is programmed to wait for this avatar to load before confirming a session, the entire login process grinds to a halt. A purely cosmetic feature thereby compromises the core business operation.

To preempt such failures, we employ the bulkhead pattern. This involves isolating thread pools and connection pools specifically for different dependencies.

In an e-commerce context, your “Inventory Service” and your “User Reviews Service” should never share a common database connection pool. If the Reviews service experiences an onslaught from data-scraping bots, it must not monopolize resources essential for querying product availability.

We rigorously enforce timeouts and implement Circuit Breakers. Should a non-essential dependency consistently fail (e.g., more than 50% of requests), we immediately cease calls to it and return a predefined default value (such as a generic avatar or a cached review score).

Crucially, for high-throughput services, we favor semaphore isolation over thread pool isolation. Thread pools introduce overhead due to context switching. Semaphores, conversely, simply cap the number of concurrent calls permitted to a specific dependency, instantly rejecting surplus traffic without queuing. The primary transaction must endure, even if peripheral systems are struggling.

3. Mitigating the Thundering Herd via Request Collapsing

Consider a scenario where 50,000 users simultaneously load the homepage at precisely the same moment (e.g., at kick-off or a product launch). All 50,000 requests hit your backend, seeking identical data, such as “What is the metadata for the Super Bowl stream?”

Permitting all 50,000 requests to directly access your database would inevitably overwhelm it.

While caching is the apparent solution, conventional caching mechanisms are often insufficient. You remain susceptible to the “Cache Stampede.” This phenomenon occurs when a widely requested cache key expires. Suddenly, thousands of concurrent requests detect the missing key, and all of them rush to the database simultaneously to regenerate it.

To counteract this, we implement request collapsing (also frequently referred to as “singleflight”).

When a cache miss happens, the initial request proceeds to the database to fetch the required data. The system recognizes that 49,999 other users are requesting the exact same key. Instead of directing them all to the database, it places them in a waiting state. Once the first request successfully returns, the system populates the cache and then serves all 50,000 users with that single, retrieved result.

This pattern is crucial for “flash sale” scenarios in retail. When a million users repeatedly refresh a page to check product stock, performing a million individual database lookups is untenable. Instead, you perform one lookup and distribute that single result to everyone.

We also employ probabilistic early expiration (or the X-Fetch algorithm). Rather than waiting for a cached item to completely expire, we proactively re-fetch it in the background while it is still considered valid. This strategy ensures users consistently access a “warm” cache and prevents the triggering of a cache stampede.

4. The ‘Game Day’ Rehearsal

The architectural patterns discussed above remain purely theoretical until subjected to rigorous testing. In my experience, during a crisis, one does not magically rise to the challenge; rather, one performs at the level of their preparation.

For events like the Olympics and the Super Bowl, we don’t merely hope our architecture will hold up. We intentionally destabilize it. We conduct intensive game days where we simulate enormous traffic surges and deliberately introduce failures into our production environment (or a high-fidelity replica).

We systematically simulate specific disaster scenarios:

- What unfolds if the primary Redis cluster abruptly disappears?

- What happens if the recommendation engine experiences a severe latency spike, increasing to 2 seconds?

- What is the impact if 5 million users attempt to log in within a mere 60 seconds?

Throughout these exercises, we rigorously validate that our load shedding mechanisms activate as designed. We verify that our bulkheads effectively contain failures and prevent widespread impact. Frequently, we discover that a seemingly innocuous default configuration setting (such as a generic timeout in a client library) can inadvertently undermine all our painstaking architectural efforts.

For leaders in e-commerce, this translates to conducting stress tests that exceed your projected Black Friday traffic by at least 50%. You must precisely pinpoint your system’s “breaking point.” If you don’t know the exact number of orders per second that will incapacitate your database, you are simply not prepared for the event.

Resilience: A Mindset, Not a Tool

You cannot purchase “resilience” off-the-shelf from AWS or Azure. These complex challenges are not resolved merely by migrating to Kubernetes or horizontally scaling with more nodes.

Achieving the “Super Bowl Standard” necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of how failures are perceived. We operate under the assumption that components will inevitably fail. We anticipate network slowdowns. We expect user behavior to, at times, resemble a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack.

Whether you are developing a streaming platform, a banking ledger, or a retail storefront, the ultimate objective is not to construct a system that never breaks. The goal is to build a system that breaks partially and elegantly, ensuring that its core business value remains intact.

If you postpone testing these critical assumptions until live traffic surges, you will find it is already too late.

This content is presented through the Foundry Expert Contributor Network.

Interested in participating?